Gondolier by Neil

Via Flickr:

One of may favourite photos from Venice. Each gondolier that passed this spot did a little kick off the wall like this guy. I also love that he’s on his phone.

paperhound:

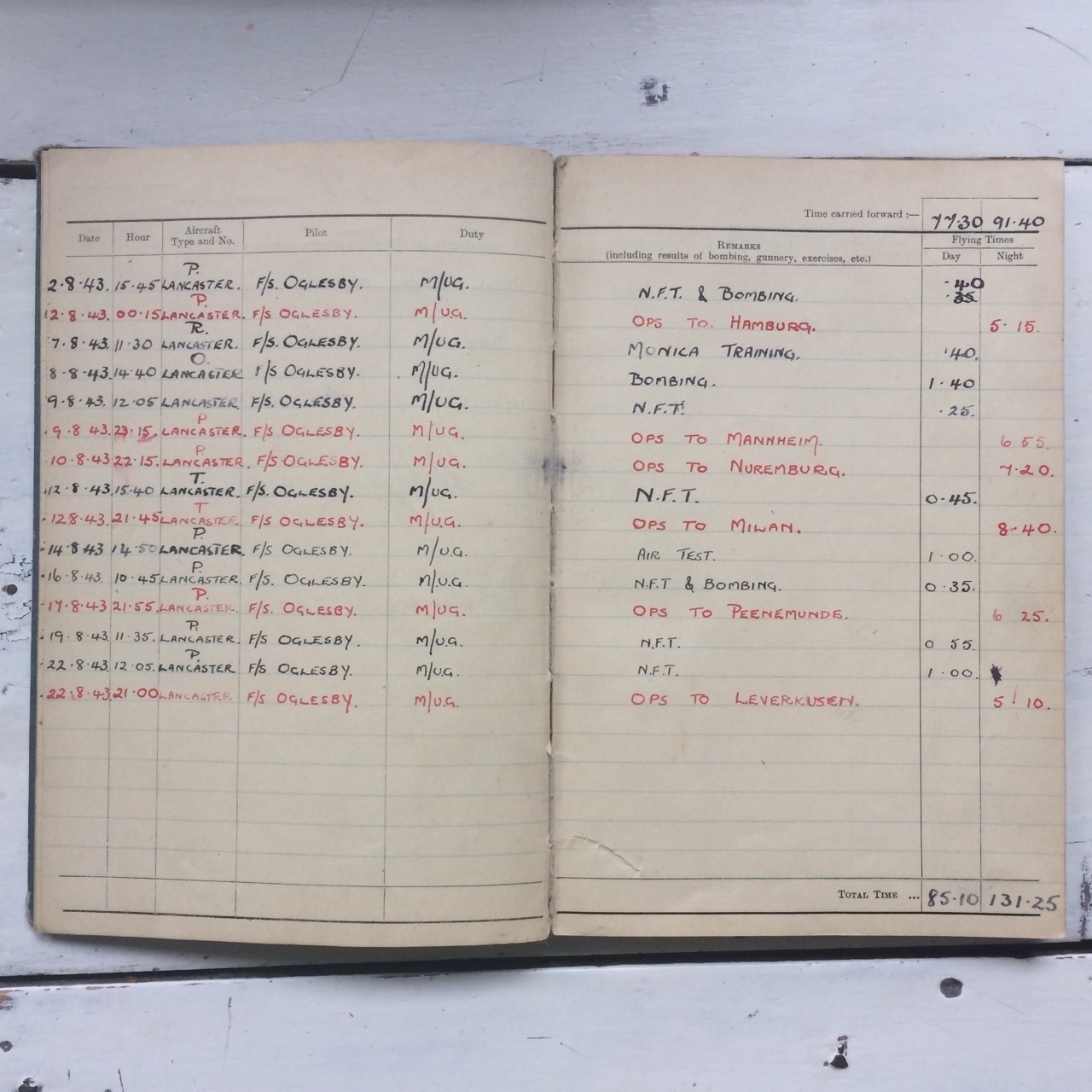

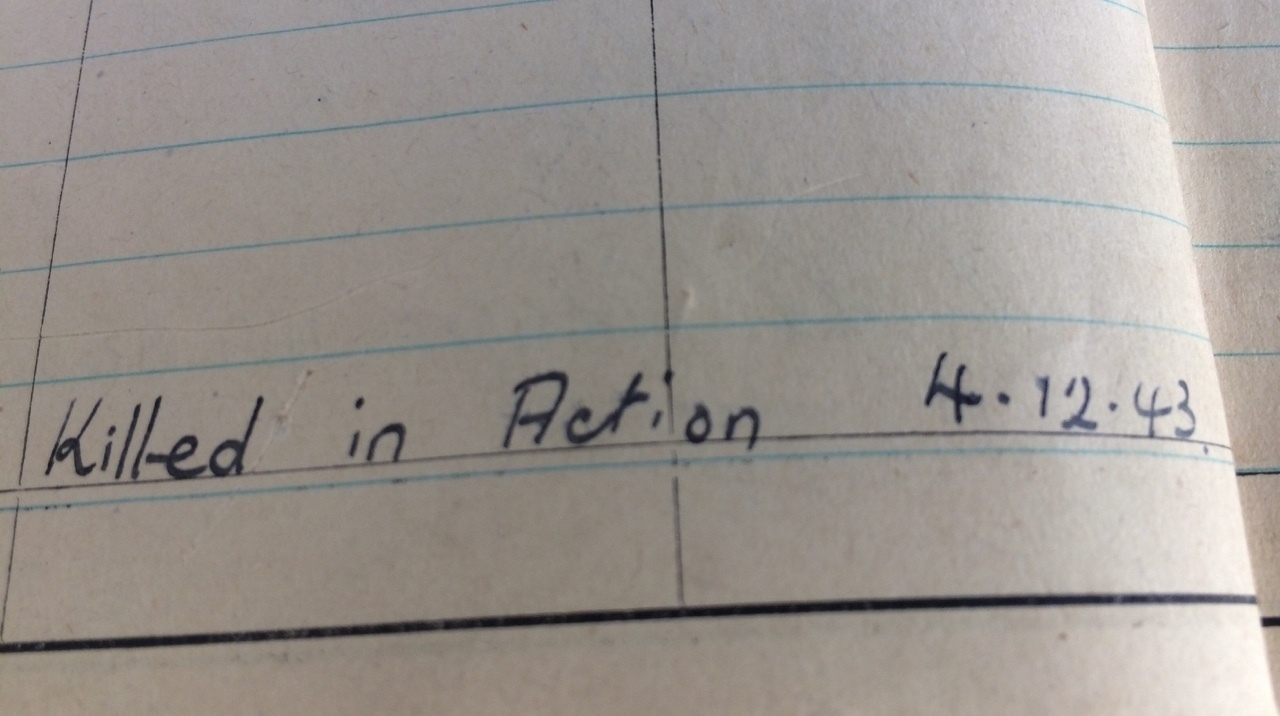

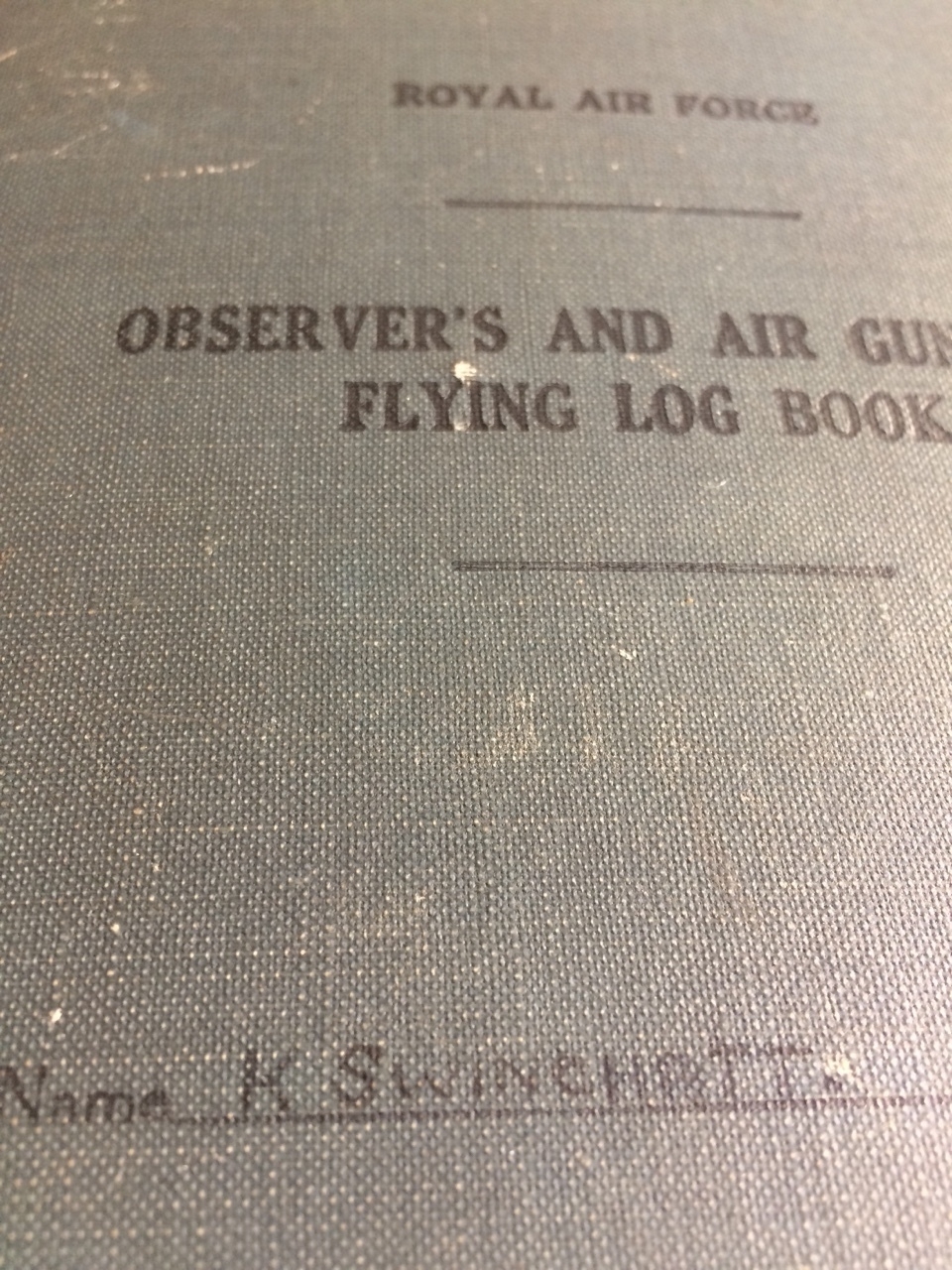

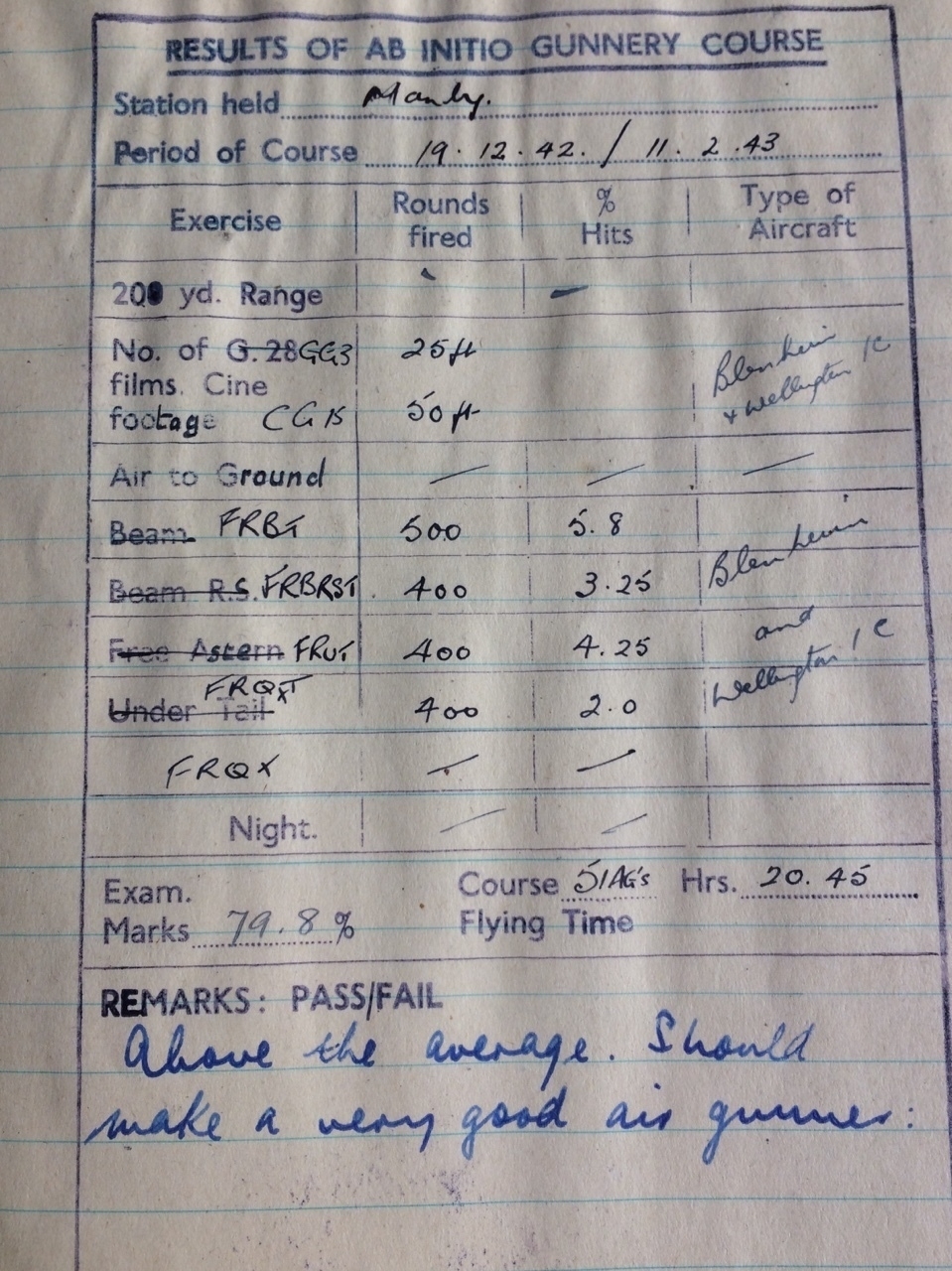

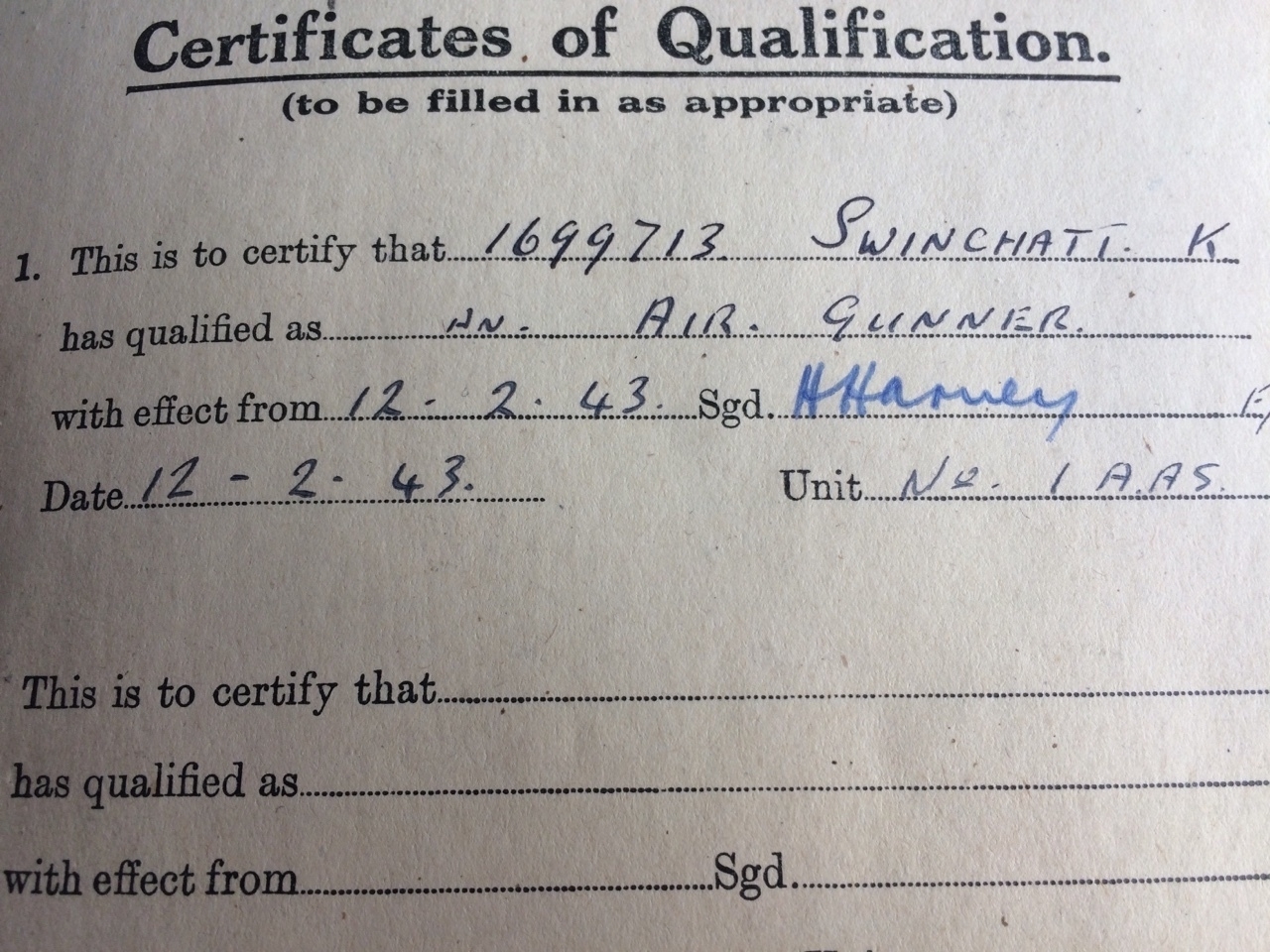

Of course there are so many narrative strategies to achieve the kind of surprise ending that delivers shock and tragedy in a single blow, but twenty-year old RAF gunner Kenneth Swinchatt’s daily line-entries, tidily recording in block letters his flying hours until abruptly interrupted by a different hand on December 4th, is especially jarring for its combination of banal bureaucratic repetition and the humanity of handwriting - a year’s worth of everyday record-keeping, and then the sudden end. He was one of a six-man crew flying a Lancaster heavy bomber that took off from East Kirkby at 0031 hrs on 3 December, 1943 for operations in Leipzig. Crashed at Volgfelde, south of the railway line between Gardelegen and Stendal. Real physical history of a real person.

nowness: NOWNESS Shorts: And So We Put Goldfish In The Pool A Sundance award-winning coming-of-age story replete with suburban hopelessness and adolescent rebellion